I grew up in San Luis Obispo, a small town about 20 miles inland from the Pacific Ocean in central California. I was raised primarily by my grandmother, Anna Herrera. She was a very affectionate woman who liked to tell jokes and stories and take walks along the river behind her small house.

But there was one thing we hardly ever talked about. I knew we were Salinan Indian, but — scarred by a history of racism and oppression endured by her family — she rarely brought up what happened to us.

The Salinan suffered what all California Indian tribes went through: genocide. Spanish missionaries came in the 18th century and forced them into slavery to build 21 missions that still line the state. In 1849, the gold rush brought settlers from the east into California and drove many Indians from their traditional hunting and gathering places.

The situation turned dire in 1851 when Gov. Peter Burnett declared during his state of the state address that “a war of extermination will continue to be waged between the races until the Indian race becomes extinct.” Many, including our own Salinan people, hid in plain sight, taking on Spanish names.

Losing ancestral lands

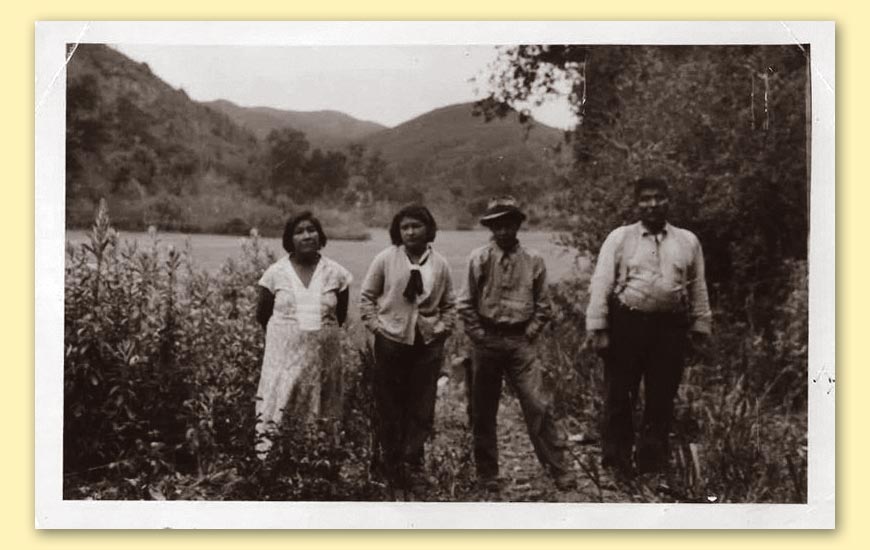

In 1997, I was in my early 20s and working on a short film about my then-76-year-old grandmother. I asked her to take me to where many of our ancestors are laid to rest: a place called Toro Creek, nestled in the Santa Lucia mountain range. With gorgeous views stretching from the mountains to the sea, it’s prime California real estate…

READ FULL ARTICLE

Courtesy of Allison Herrera